PREPARATION FOR Chancellor Reeves’ first Budget in the United Kingdom, due on Wednesday, has brought much chatter about what should happen, or rumours about what is planned, next week. This includes the usual vested interest-complaints about the adverse impact of rumoured tax hikes as well as “thought leaders” telling us the correct way to rework the fiscal rules. We have even had former BOE Governor King mansplaining—as Reeves’ former boss, he likes to remind us—what she should do (behind a paywall).

But it is certainly true that this Budget is a huge occasion for the UK economy, as a look at the fiscal inheritance reveals.

An expanding state

UK government spending jumped sharply during the pandemic, under the most recent Conservative government, and failed to fall back again once the emergency had passed.

The latest IMF World Economic Outlook database shows public expenditure-to-GDP (excluding interest payments) in the UK jumped from roughly 37% of GDP in 2019 to 41% in 2024—a 4ppts increase in general government non-interest expenditure.

Of course, spending had to rise during the pandemic—just as GDP had to contract as social distancing was enacted. But the logic at the time, though perhaps not made explicit, was that expenditure would temporarily increase. Once the pandemic had passed it would revert back to pre-pandemic levels once more.

Or so it was assumed.

Instead government spending has remained at a structurally higher level.

Mission creep?

Why might spending increase as a share of GDP merely as a result of the pandemic? One possibility is that there is something going on with the deflators.

Imagine public expenditures are indexed to the consumer price index—which can differ from the GDP deflator. Again consulting the WEO, CPI increased by 24.3% from 2019 to 2024, whereas the GDP deflator increased “only” 21.4%—so there is roughly a 3ppts gap, with CPI exceeding the GDP deflator.

A little maths shows that if non-interest expenditure is indeed indexed to CPI, then with unchanged volume of government expenditure, nominal expenditure would therefore rise by 1.2% of GDP between 2019 and 2024 (roughly, the expenditure share multiplied by the inflation differential).

So the sharp rise in consumer prices during the pandemic has played a role. The problem is, this only explains at most one-third of the non-interest expenditure increase since 2019.

We are left with the possibility that the volume of general government expenditure has structurally increased.

One way to see this is to look at the share of public sector employment in total employment. And we see that after peaking at 25% of total in 2009, public sector employment fell to 21½% from 2017-2019. But during the pandemic public sector employment jumped once more to 24% in 2023Q1 and has showed little sign of normalising since—this despite total employment as of 2024Q2 being exactly the same as in 2019Q4 at 32.9 million.

Put another way, there are roughly 9% more public sector workers today than in 2019Q4—and 6½% more than 2009Q4.

What happened during the pandemic?

One possibility is that public spending “got out of control” needs to be brought to heel once more. Alternatively, it might be that the “austerity years” were the aberration—when public sector service provision was unsustainably squeezed. Like a coiled spring, public sector employment rebounded during the pandemic to reflect the true state of pressure on public service provision in the United Kingdom.

A crazy inheritance

This explains the importance of the Reeves’ Budget.

The choice is between a return to austerity or adjusting tax receipts to the true state of public service provision.

Despite presiding over the expansion in the size of the state, the out-going Conservative government left a Budget which assumed, without a clear plan, a huge real-terms cut in public expenditure once more—with current expenditure dropping about 3ppts of GDP and receipts increasing about 1ppts, as in the chart below.

On top of this, net investment was projected to drop from 2.4% of GDP this financial year to 1.7% of GDP by 2028-29.

It may not be hyperbole to claim that after the previous decade, the possibility of delivering another heavy dose of austerity, baked into the previous Budget document, would be impossible for the population to stomach.

If, as some think, the Brexit vote was a consequence of the previous austerity squeeze, what would happen after 5 more years of austerity?

But what are the options? Instead of a Budget that relies mainly on squeezing public sector services, the only other choice is to raise real revenues.

Imagine instead a Budget that raises taxes by GBP30bn per year while freezing current expenditure and net investment in % of GDP. If so, we get a path for public sector net borrowing (PSNB, with all other assumptions on student debt etc. held constant) which sees an initial fall in public borrowing in 2025-26 (from GBP88bn in the March Budget to GBP75bn and overall deficit of 2.6% of GDP from 3.0% of GDP expected.) But thereafter, PSNB remains in the range GBP75-80bn per year—or roughly 2.5% of GDP across the horizon (instead of falling to 1.2% of GDP in 2028-29.)

The main challenge for Reeves, then, is that Labour is committed not to raise taxes on “working people”—which has raised questions about what the definition of working people should be.

But it seems likely that the increase in current revenues, assumed at GBP30bn per year, will come about through an increased burden on businesses and wealthy households.

What fiscal rules?

Such an up-front adjustment in taxes has the benefit of allowing Chancellor Reeves to meet the first of her fiscal rules that requires current spending to balance—so there cannot be borrowing for day-to-day spending, only for (net) investment.

Crucially, notice the definition of current budget includes capital depreciation. So current receipts must cover current spending plus capital depreciation of about 2.5% of GDP per year.

Then there is the question of the debt rule.

There has been considerable pressure to reconsider moving to a net worth rule for a number of reasons.

First, to avoid a repeat of the 2010s. Public sector net investment fell from 2.4% of GDP in 2010-11 to 1.7% of GDP in 2015-16 despite a growing population. This is exactly the same as the assumption baked into the March Budget projections from 2024-25 to 2028-29. Yet to need to invest in schools, transport, and hospitals is immense—not to mention the need to adapt to emerging new technologies. A fall in net investment would be irresponsible.

Second, a number of high profile commentators have advocated moving to a net worth rule. This includes an IPPR report, including a foreword by Jim O’Neil, suggests that a net worth metric would be appropriate. O’Neil notes: “Focusing on a more comprehensive debt metric – such as public sector net worth – would provide greater room for borrowing to invest in line with a more transparent approach to fiscal rules. It would also bring fiscal rules more in line with how financial markets think about fiscal sustainability.” Meanwhile, former BOE Deputy Governor Andy Haldane, writing in the Financial Times recently, puts it as follows: “The most growth-friendly fiscal rule is, by contrast, one which recognises the illiquid assets yielding the highest growth and tax dividend. This is defined in terms of public sector net worth. That would create about £50bn of extra fiscal headroom per year — more if the time horizon for meeting the fiscal rule was a more sensible 10 years rather than the current five.”

The problem with targeting PSNW, however, is that it would involve projecting non-financial assets such as land and housing. How are these projected? The OBR explains their “estimate for land … assume[s] that the value of land rises in line with house prices.”

The value of government-owned land in net worth is about GBP0.5 trillion. Land prices were projected to increase at 3.4% and 3.7% in the last two years of the forecast horizon at the last Budget. As such, this implies an improvement in PSNW of about GBP18bn in value per year at the end of the horizon.

If Reeves were to shift to targeting a decline in (the negative of) PSNW as the debt rule, this creates additional space each year simply linked to the projected increase in house prices!

Perhaps this explains why it was rumoured last week that Reeves is considering instead of moving to public sector net liabilities (PSNL). This rule would include financial assets, such as student loans, government deposits, and equity holdings. But it would not benefit from revisions to house prices which might otherwise impart a bias towards debt issuance.

Given the market reaction to this rumoured change in rules, which saw gilts marginally underperform global rates but no pressure on sterling, it seems that the initial response to the proposed change is muted. And on Budget day, if there is an initial contractionary impulse as tax increases take hold and near-term net issuance shrinks, then rates will price in a more aggressive cutting cycle—so no repeat of the Truss-Kwarteng mini-budget crisis.

Conclusions

Chancellor Reeves faces a huge dilemma in the Budget next week. She is boxed in.

First, no more austerity. Second, more investment than planned in the March Budget as well as current spending for departments. Third, no taxes on “working people.”

Meanwhile, Reeves is being told a new net worth rule would be more like “how the markets think.” But the Truss-Kwarteng experience lives on the public conscience so she will not want to risk another market blow-out.

One way to meet these constraints, outlined above, is through a near-term adjustment in net borrowing due to an increase in taxes on corporates and wealthy households—while showing larger fiscal deficits from 2026-27 as investment spending ramps up and current spending remains stable.

This would stabilise the overall budget deficit at about 2.5% of GDP instead of contracting close to 1% of GDP previously.

And a change in the debt rule to target public sector net financial liabilities would be a compromise between the more expansive PSNW rule and current arrangements. Initially, stabilising net investment as a share of GDP would be a downpayment while the market reaction is tested. Later this parliament, as circumstances allow and the next election comes into view, Reeves can be more ambitious still on public investment.

Annex: How large is the pie?

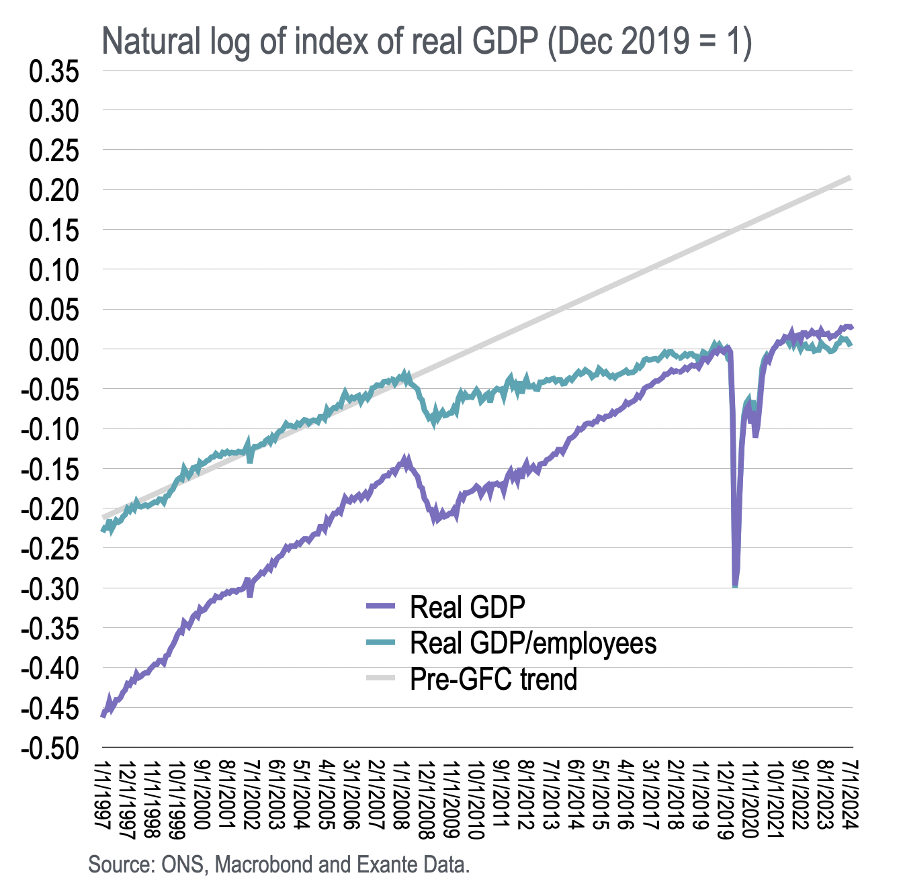

The chart below shows (the natural log of) an index of real GDP and real GDP per employee in the UK since 1997. It shows GDP taking a leg down during the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) while the growth rate of GDP per employee (given by the slope of the chart) also slowed in its aftermath.

GDP also fell sharply during the pandemic, of course.

Since recovering, real GDP per capita is today roughly at the end-2019 level. That is, there is been no increase in output per worker since the pandemic.

Put another way, although the real resources available to the community today is no smaller than before the pandemic, we are no better off in the aggregate. And since the size of the state is larger, to lock in a larger government real after tax income will have to be squeezed.

The content in this piece is partly based on proprietary analysis that Exante Data does for institutional clients as part of its full macro strategy and flow analytics services. The content offered here differs significantly from Exante Data’s full service and is less technical as it aims to provide a more medium-term policy relevant perspective. The opinions and analytics expressed in this piece are those of the author alone and may not be those of Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC. The content of this piece and the opinions expressed herein are independent of any work Exante Data Inc. or Exante Advisors LLC does and communicates to its clients.

Exante Advisors, LLC & Exante Data, Inc. Disclaimer

Exante Data delivers proprietary data and innovative analytics to investors globally. The vision of exante data is to improve markets strategy via new technologies. We provide reasoned answers to the most difficult markets questions, before the consensus.

This communication is provided for your informational purposes only. In making any investment decision, you must rely on your own examination of the securities and the terms of the offering. The contents of this communication does not constitute legal, tax, investment or other advice, or a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security. Exante Advisors, LLC, Exante Data, Inc. and their affiliates (together, "Exante") do not warrant that information provided herein is correct, accurate, timely, error-free, or otherwise reliable. EXANTE HEREBY DISCLAIMS ANY WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED.

Thanks for this. Good article let down by failure to correct errors by re-reading before publishing, some of which obscure meaning of the sentence in question. Not a massive deal but for me, you lose a bit of authority in your general viewpoint by making such a basic mistake.